Picture this: It's 1972, and Walt Disney Company is the darling of Wall Street. Disneyworld's Florida gates have just swung open, the animation studio is thriving, and investors can't get enough. Disney stock commands a staggering price-to-earnings ratio (also known as a PE ratio) of 71 – nearly four times higher than the S&P 500's price-to-earnings ratio of 19. The market's message is clear: Disney is special. It is one of the Nifty Fifty stocks and deserves a high multiple.

Fast-forward to today. Those bullish investors weren't wrong about Disney's potential. A $10,000 investment in 1972 would have grown to over $1 million by 2025 with dividends reinvested—a respectable 9.2% annual return.

But there was a catch. From 1972 to 1974, that $10,000 investment in Disney had shriveled to $3,000. Investors who were excited about Disney’s prospects in 1972 needed to wait 13 long years just to break even.

(Returns calculations from https://dqydj.com/stock-return-calculator/)

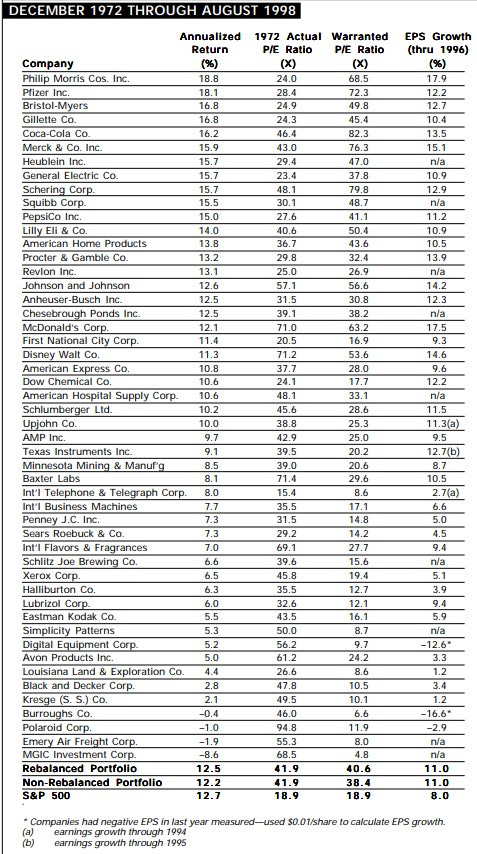

The Nifty Fifty

During the late 60’s and early 70s the Nifty Fifty were the best, most popular stocks in America. Some of these were names you know today like Pfizer, General Electric, and Coke while some of the others no longer exist. However, at the time, these companies were all considered to be so good that it was thought nothing bad could ever happen to them and therefore no price was too high for their stocks.

Until that stopped being true. From 1973-74 the stock market as a whole declined by about 50% and the Nifty Fifty stocks were hit the hardest. In many cases, their price/earnings ratios fell from the range of 60 to 90 to the range of 6 to 9.

But eventually, according to Jeremy Segal’s research summarized in the chart below, given enough time (in this case 26 years), most of these companies came back and justified their initial valuations.

Unfortunately, great companies or not, most investors didn’t survive the short-term and therefore didn’t benefit from the long-term.

Why is this important?

Howard Marks has three principles for investing in equities:

It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay that counts.

Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.

There’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous, and there are few assets so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.

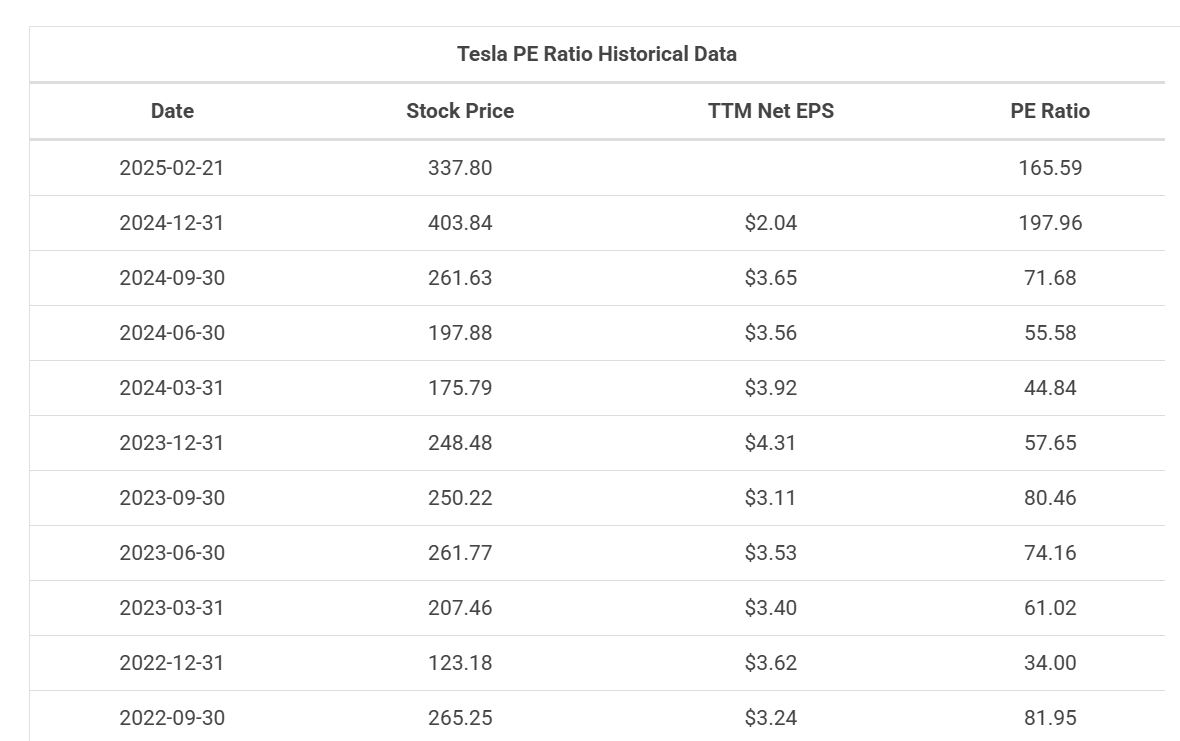

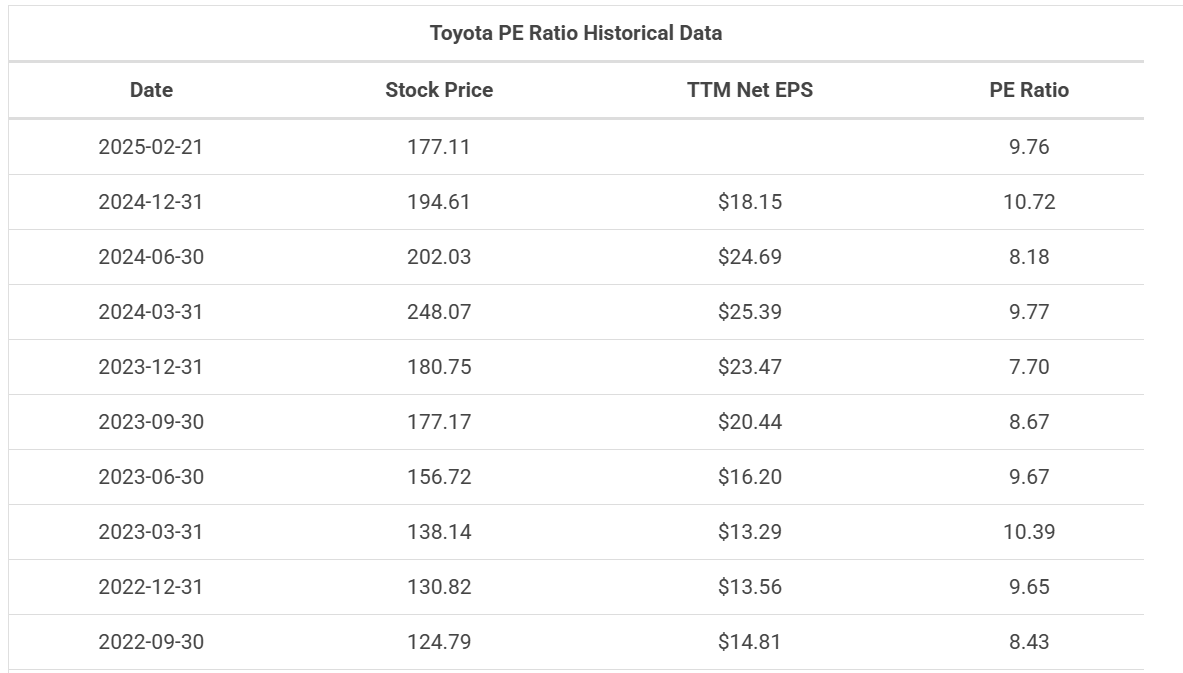

For example, Tesla is a great company, but it currently trades with a P/E ratio over 150.

Fifty years from now, we may look back at a chart like the one above and say that was a steal, but maybe not. For comparison, Toyota has a P/E ratio of 9.

Tesla may be a better company than Toyota, but if Tesla’s stock traded at the same multiple as Toyota's, Tesla shares would lose 95% of their value in the blink of an eye.

If the multiple dropped to 50 (roughly where Nvidia trades), Tesla’s share price would fall 70%.

Tesla could do all the amazing things analysts and investors expect it to—just like Disney did—and the shares could still lose incredible amounts of money.

This is why you can never forget that great companies and great stocks are often two very different things.

I recorded a webinar reviewing the slides I sent over last week. This was a test run with lackluster audio, but we are playing with some tools and formats that will allow us to provide options for those who can’t attend in-person events in the future. Feel free to check out the video here.

A copy of the slides can be downloaded here.

When it comes to writing about investments, the disclaimers are important. Past performance is not indicative of future returns, my opinions are not necessarily those of TSA Wealth Management and this is not intended to be personalized legal, accounting, or tax advice etc.

For additional disclaimers associated with TSA Wealth Management please visit https://tsawm.com/disclosure or find TSA Wealth Management's Form CRS at https://adviserinfo.sec.gov/firm/summary/323123